Yinka Shonibare, the British Nigerian artist whose work “explores cultural identity, colonialism and post-colonialism within the context of globalisation” said it best: “[African] fabrics are not really authentically African the way people think . . . They prove to have a crossbred cultural background quite of their own. And it’s the fallacy of that signification that I like.” Shonibare’s statement provides helpful context within which we may consider the abiding and ever growing trend of designing with Wax Print — that Dutch fabric that was originally created for an Indonesian market, and which is also known as Ankara (not to be confused with the Turkish capital city), and that is so well worn and well loved in parts of the Motherland, that it has come to be known as African Print.*

Yinka Shonibare, the British Nigerian artist whose work “explores cultural identity, colonialism and post-colonialism within the context of globalisation” said it best: “[African] fabrics are not really authentically African the way people think . . . They prove to have a crossbred cultural background quite of their own. And it’s the fallacy of that signification that I like.” Shonibare’s statement provides helpful context within which we may consider the abiding and ever growing trend of designing with Wax Print — that Dutch fabric that was originally created for an Indonesian market, and which is also known as Ankara (not to be confused with the Turkish capital city), and that is so well worn and well loved in parts of the Motherland, that it has come to be known as African Print.*

The etymology of each of the names above (and below) provides clues about the history of this now ubiquitous textile. The fabric was originally created by the Dutch (as early as 1846) in an effort to replicate and mass produce traditional Javanese or Batik wax print from Indonesia (what was then the Dutch East Indies)—to sell to the Indonesian consuming public. The English, who had just experienced enlightenment via the Industrial Revolution, joined in on the production of these fabrics as well—using mechanised tools such as the the cotton gin and power loom, and power derived from steam. While it is unclear how Dutch knock-offs of Indonesian fabric bound for the Indonesian archipelago ended up in West Africa (maybe via the Black Dutchmen), we have the Africans, specifically Ghanaians, to thank for bringing this print to vogue.

The etymology of each of the names above (and below) provides clues about the history of this now ubiquitous textile. The fabric was originally created by the Dutch (as early as 1846) in an effort to replicate and mass produce traditional Javanese or Batik wax print from Indonesia (what was then the Dutch East Indies)—to sell to the Indonesian consuming public. The English, who had just experienced enlightenment via the Industrial Revolution, joined in on the production of these fabrics as well—using mechanised tools such as the the cotton gin and power loom, and power derived from steam. While it is unclear how Dutch knock-offs of Indonesian fabric bound for the Indonesian archipelago ended up in West Africa (maybe via the Black Dutchmen), we have the Africans, specifically Ghanaians, to thank for bringing this print to vogue.

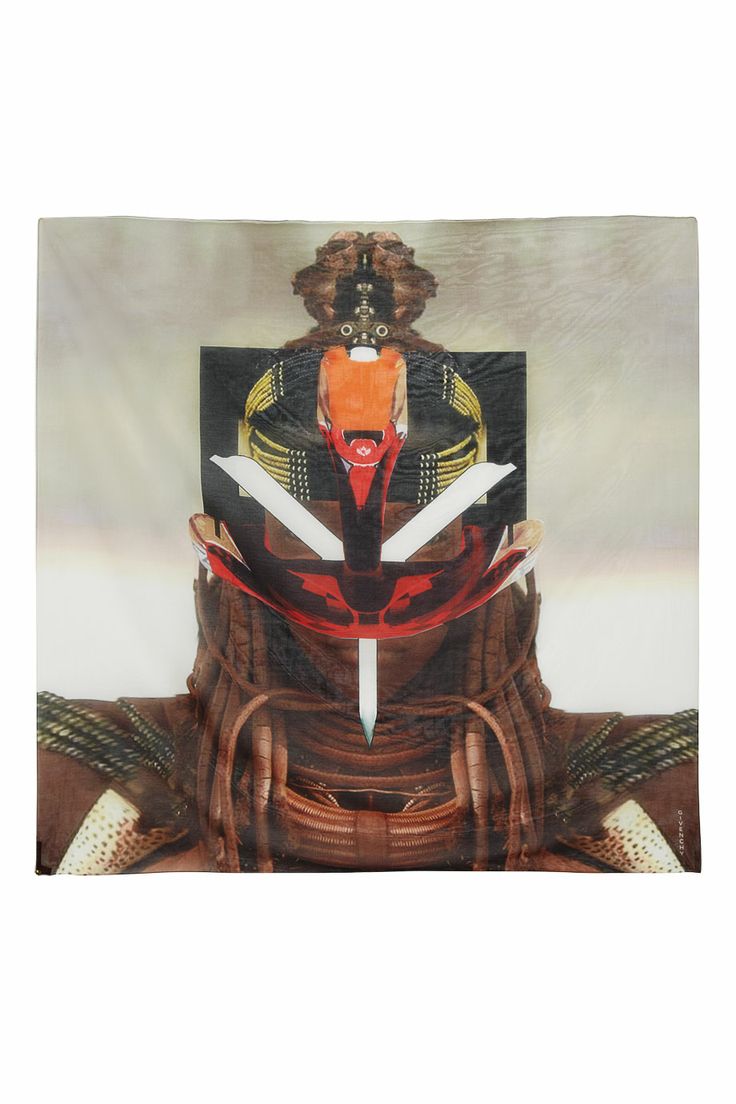

Thinking about the Dutch and their plans to economically exploit one colony (by mass producing traditional art), which then lead to their subsequent entrenchment into another colonial market (albeit one with which it eventually collaborates creatively) sends shivers down my spine. Could this be why artists such as Yinka Shonibare and Kehinde Wiley (each of Nigerian descent) incorporate Wax Prints into their art—art which is so deeply rooted in the traditions of European art history, but which showcases the textile as symbol for Africa so assertively?

Thinking about the Dutch and their plans to economically exploit one colony (by mass producing traditional art), which then lead to their subsequent entrenchment into another colonial market (albeit one with which it eventually collaborates creatively) sends shivers down my spine. Could this be why artists such as Yinka Shonibare and Kehinde Wiley (each of Nigerian descent) incorporate Wax Prints into their art—art which is so deeply rooted in the traditions of European art history, but which showcases the textile as symbol for Africa so assertively?

Kehinde Wiley x Yinka Shonibare. Photo by @Tee_Tos, taken during Art Basel, Miami 2014

Kehinde Wiley x Yinka Shonibare. Photo by @Tee_Tos, taken during Art Basel, Miami 2014

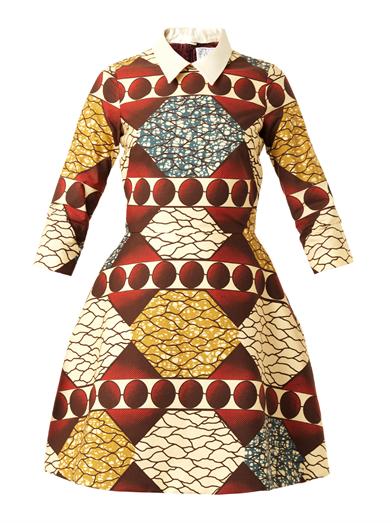

I started thinking about Wax Prints earlier this evening, after seeing Beyonce’s Instagram photos that are featured in this article. Initially, I thought her top was designed by Chen Burkett New York (a company from which I purchased a very similar top), but later realized that it was made by Reuben Reuel of Demestiks New York (buy here). As you’ve no doubt observed, African Print textiles are now the bases of innumerable designs the world over. But, as far as the African market is concerned, despite the rise of cheaply produced Wax Print from China and locally sourced Wax Print from African based artisans, the most prestigious Wax Prints are still produced in The Netherlands, by a Dutch company (Vlisco) that has supplied fabric to Africa for more than a century. Check out how the print is used by designers such as Stella Jean, Suno and Autumn Adeigbo and purchase your own African/Dutch Wax Print piece from the StyleChile Shop. Let us know if you think this fabric is authentically African or nah?

* In addition to the more common names above, African Print is also known as Real English Wax, Veritable Java Print, Guaranteed Dutch Java and Veritable Dutch Hollandais.

* In addition to the more common names above, African Print is also known as Real English Wax, Veritable Java Print, Guaranteed Dutch Java and Veritable Dutch Hollandais.

Article by Naki. Photos of Beyonce via Beyonce’s and Reuben Reuel’s Instagram accounts. Photo of Yinka Shonibare’s work and Kehinde Wiley’s painting courtesy of @Tee_Tos’s Instagram account.

Leave a Comment

What a great article! So interesting, NAkia!

[…] no blue suits. Just women, really beautiful women, in linen, though it is only almost-spring, and Dutch Indonesian Ghanian Print Blazers, and black lace back cut-outs, and some […]